Interview: Ken Marcus (part I)

Ken Marcus is a highly accomplished photographer from Hollywood, California. He’s been an icon in the world of erotic art photography for many years. He originally gained his reputation as a glamour photographer at Playboy and Penthouse magazines. For over 30 years he produced hundreds of centerfold, editorials, album covers, and commercial advertisements.

In addition to his photographic career, Ken produced lectures, educational videos and conducted workshops on the art of glamour photography. His fine-art work has been featured in galleries, books, magazines, television, and he was an artist-in-residence at the Yosemite National Park Museum.

We recently had the pleasure of spending an afternoon with Ken at his Melrose Avenue studio. In part one of this two-part interview we talk to Ken about his early career.

– Edu

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Edu: Tell us about how you got into photography, in particular the time you spent at Yosemite National Park with Ansel Adams.

Ken Marcus: Well, there were two phases of my life that involved Yosemite. One was in my early life, and the other when I was in my 40s.

I began my association with Ansel Adams by attending one of his workshops at age 12. I fell in love with photography and continued to attend workshops at every opportunity. I spent every available moment that I was away from school either in Yosemite learning the Zone System and practicing landscape photography, or in my darkroom at home developing and printing the images I shot. I attended workshops all throughout my school years and even after I opened my studio and was making my living in photography. There was a great deal to learn and experience. However, after 13 years, I began to feel like somewhat of a distraction to the class and stopped attending Ansel’s workshops.

Edu: Why did you feel like you were a distraction?

Ken: Here were these other photographers coming from all over the world to study with Ansel, and when they realized there was a Playboy photographer in their group they started asking me lots of questions that did not relate to what the workshops were supposed to be about. That was understandable, but I didn’t feel that I should infringe on Ansel’s time. So, at that point I stopped attending his workshops and the following year I began teaching seminars and workshops of my own, and continued doing so for about another 25 years.

Edu: You started so young, and with Ansel Adams no less. How did that happen and what was it like?

Ken: Ansel was an amazing human being with this wonderful grey haired wife that used to cook and bake on a wood-burning stove in their Yosemite cabin. I remember thinking of them like Santa Claus and Mrs. Claus. Of course, I never told them that.

I started taking pictures when I was about 5 years old and took to it right away. I had a small darkroom in the basement and later my dad built one for me in the garage.

At the time, I don’t think they had any idea how famous he would eventually become. This was right at a crucial point in his career, when he was recognized by the small inner circles of the fine art community, but Ansel hadn’t really become a household name yet. I was studying with him throughout many of those years as his reputation, name and publicity continued to grow. I learned an enormous amount from him, both technically and philosophically, I learned about business and the importance of self-promotion, as well as other important things that have helped me make wise decisions throughout my career.

Edu: In addition to Ansel, you also studied at the Art Center College of Design as well as Brooks Institute of Photography.

Ken: I was studying with Ansel while I was in junior high school, and then all throughout high school. The Art Center College of Design is here in Southern California, and they offered a night program. You had to be a high school graduate with a couple years of college to qualify for that. Ansel was kind enough to write a very nice letter of introduction to let these people know that even though I was very young, I could function on an adult level and recommended they allow me to attend classes there.

So, for three years I attended night classes at the Art Center College of Design. I studied fashion, product design, architectural photography, product photography, food photography, and classical nude photography—all of the same curriculum that they had for their full time students.

When I graduated high school I just assumed I would go straight into Art Center full time, but they informed me that I still needed to have two years of college. I decided I didn’t want to do that, so I went up to Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara. I attended Brooks for a few semesters, and soon felt that between what I had learned at Brooks, Art Center and Ansel Adams there was no need to continue. So, at the ripe old age of 17 I acquired my business license, began working, and then a year later I found my studio. Two weeks after my 18th birthday I moved in, and I’ve been here ever since!

Edu: That’s an impressive story. You were obviously very entrepreneurial to start a business at 17. What role did your parents play, were you following in their footsteps somehow?

Ken: I come from a family where everyone is either an educator or a doctor. My mother was a political science professor in the state university system, and everyone else in my family are either doctors or associated with the medical profession. There are no other artists in my family. I somehow ended up being the only one.

Edu: That must have been hard for them to understand. Did they even consider photography a real career? Were they supportive?

Ken: They were extremely supportive. Photography is not an inexpensive hobby for a child to have, particularly in the days of film, and the necessity to have a dark room with enlargers, and all of those costly items that go along with it.

When I was 15 or so, my father met a man named Haskell Wexler. Haskell was an award-winning cinematographer and famous director, who did a lot of movies in the ’60s and ’70s. My father was telling him about me, and that I was interested in photography. He was worried that there was no future in taking pictures for a living and asked, “Can somebody actually make a living at this?”

My father told him about my attending Art Center and the Ansel Adams workshops. Haskell was very encouraging and related what he knew about the business and how it’s important to believe in my talent and that it usually takes a long time for things to happen in the photo business.

That conversation changed my father’s attitude. At least now he knew that maybe there was hope, and that his son might actually make a living with his camera. He realized at that point, it’s not just a hobby, like he might have previously thought. That was one of those pivotal events that I look back on, that was very important in my life.

Edu: Okay, so now your family is on board, and obviously you’re already very talented, but when was the turning point where you actually started making a living and photography became your career?

Ken: I started earning money with my camera within the first month of getting my business license. I was still living at my parents house and was sharing a studio with my friend Don Carroll, who did special effects photography.

My very first job was to photograph a lamp for a local store. For whatever reason they trusted this skinny 17-year-old to photograph their lamp for a newspaper ad. I did such a good job, that I was then immediately given my second assignment, photographing their entire lamp catalog. I went from photographing one lamp to photographing 150 lamps. It put good money in my pocket, which was nice, and then as life sometimes does, you get thrown a strange curveball.

Out of the blue, my very next assignment came in as a recommendation from the lamp client to his friend that owned a burlesque theater in Hollywood. The next thing I know, I was photographing the instruction book for the Pink Pussycat College of Striptease, where beautiful women came from all over the world to learn the fine art of peeling off a glove, 20 different ways of taking off a stocking, how to tease an audience, and how to prance across the stage and all the refinements of burlesque dancing.

Edu: And you were 17-18 years old when this job came up?

Ken: I was 17 years old then. I wasn’t old enough to go into a burlesque theater as a patron, but here I was shooting the most amazing burlesque dancers for the most notorious strip joint in Hollywood. I was working with famous dancers from all over the world. Dancers in those days weren’t like anything we have today. Total nudity was completely illegal everywhere in America, but for a 17-year-old, it was still more than anything I had encountered before. Funny how things work out!

From there I went on to shooting more lamps, products, architecture, advertising and food. I think I made more money shooting food on a daily basis than any other kind of assignment I ever did.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Edu: We know you eventually went on to shoot for Penthouse, which I assume was far more controversial back then. Did it ever get in the way of your commercial work?

Ken: Not to any real extent. I’m sure that some of the women I was working with at ad agencies might have been uncomfortable if they knew I was shooting for Penthouse, but it never came back to bite me in the butt or anything, and no one ever confronted me or said “You’re an evil, horrible person.” I’m not sure any of my commercial clients even knew what I was doing.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Edu: Speaking of Penthouse, tell us about your time there. What inspired your use of soft-focus photography, and how did you do it?

Ken: When I started working at Penthouse in the early 70s they had very low budgets. My reason for working with them was because I thought it would be fun. It seemed like a nice excuse to shoot pretty naked girls one weekend a month, and I figured it wouldn’t really interfere with my commercial work. However, I was a little concerned because I wasn’t sure how people would respond to my shooting nudes. I wasn’t smart enough back then to think, “Geez, maybe I should just use another name like most other people in this line of work do.”

Instead, I thought I’d disguise my style so no one will know the work is mine, which was very stupid because I didn’t really have a style at the time. I was doing the same sort of photography as everyone else was doing at the time—sharp, crisp, well-lit images, with all information available within the image. That’s what everybody was doing and that’s just what I was doing as well.

I thought about what I could do to make my pictures different from all the others. The first challenge was to make the models and backgrounds look beautiful and sexy. Keep in mind that we didn’t have adequate budgets for fancy locations, wardrobe or nice props. The other problem was to hide that fact and still produce fantasy images on a really low budget.

The solution seemed to be the old fashioned, out of date technique of soft-focus imagery.

I had remembered an image that Ansel Adams had done on an 8×10 view camera with an old Kodak soft focus lens from the 1920s. Everything had this soft glow to it, and the highlights were bursting and burning out. It seemed sexy for some reason even though it was just rocks, trees and water. I thought, what better way to hide the lack of good makeup and props than to use a soft focus technique and concentrate on the sensuality of the model and the sexuality of the model? Let everything else blur out.

I remembered Ansel saying that you can achieve that effect without using a heavy, expensive soft-focus lens by putting a skylight filter in front of your lens and rubbing a little Vaseline on it.

So, for my very first Penthouse layout, I did just that, and Bob Guccione (founder and owner of Penthouse) loved the results and encouraged me to do more. For the next three years almost every layout I did was soft focus. Actually, it’s not really soft focus. Your focus still has to be on, but it’s diffusion. Being out of focus is much different than being diffused, but a lot of people don’t get that. Those diffused images became known as the “Penthouse look” and that different style of imagery rapidly became very popular and gave my name a lot of national exposure.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Later on I began experimenting with fabric and cloth because I heard somewhere if you stretch a silk stocking over a lens it will create a diffusion effect. I found a variety of stocking material, and loose weave scarf material in black, because white flared things out. Flesh color was nice for some things but it threw the contrast off. Black stockings and loose weave scarf material worked best for me, so I made a series of diffusion filters like that, and continued to use those for many years. Almost everything I shot for Playboy for 11 years was with those black scarf-type diffusers.

Edu: So the inspiration for that technique, came in part from Ansel, but what about the other ones? This was long before the Internet, how did you come up with these ideas?

Ken: I don’t suddenly wake up and think, “Oh this is new, this is different, and this is what I’m going to do next.” I mean, I might wake up in the morning with that, but it’s because when I went to bed I were thinking of ten other things that also could have gelled together.

We don’t live in a vacuum; you have to learn from somewhere. I’ve always felt that everything I’ve ever done, or whatever I’ve ever come up with, has been a result of learning from others. That realization motivated me to get into the teaching aspect of photography where I could pass on the information I’ve learned. I feel that if you learn something that benefits your life, there is an obligation to pass that information on to others.

Edu: Some people are reluctant to share knowledge, like they’re scared of revealing the secret to their success, or they view everyone else as competition.

Ken: I believe in passing on what I have learned from others. When I take the time to instruct others in what I do, it clarifies in my mind what it is that I really do. Passing on the information benefits me in that way. Sometimes you don’t really appreciate the intricacies of what you do, until you try to teach it to others. Besides, knowing something in a technical realm doesn’t really make you successful. You may be very talented, with strokes of occasional brilliance, but if you can’t manage or deal with people, your work will never be seen, it’s just not going to happen. Being successful in business requires people skills, and for some reason a lot of people just don’t get it. Success is the proper combination of talent, technique, people skills, and a lot of luck.

Photo of Ken Marcus by Tom Zimberoff

Ken: When Bob Guccione first spoke to me about shooting for him I asked what the budget was for a pictorial. He said we have $250, and that has to include the model. At first that sounded ridiculous, because I was making thousands of dollars a day shooting food ads, but then I reasoned that it might be fun, and would be a good excuse to shoot more nudes.

I almost decided to say no because of the low budget. Then all of a sudden out of nowhere, I got this inspiration from something Ansel Adams once told me, “It’s okay to give your pictures away for free as long as you get a photo credit on the page with the pictures.”

So I followed my instincts and said to Guccione, “Okay I’ll do it, but I want a photo credit on the first page of each pictorial.” All I was expecting was small text on the bottom of the page that said “Photo by Ken Marcus.” In those days photographers did not get photo credits on the pictures unless it was a big deal, like some photographer for Life magazine covering a war somewhere. Everybody else had photo credits listed in a box in page 3. Sometimes you couldn’t even figure out which photographer took which pictures. That’s what publications did in those days.

So I asked for a photo credit and Bob said, “Sure, no problem.” When my first issue of Penthouse came out in the U.S., I was very surprised and amazed. Instead of a single right hand page that would open up into a layout, which was standard in those days. It was a double page spread with one picture covering both pages, which also was really rare and highly unusual at that time, and right through the middle of the picture, in text that was ¾ of an inch high, it said “Photographed by Ken Marcus.” It blew me away. I was not expecting that.

For the next three years each of my layouts had these giant photo credits on them. With the overnight success of Penthouse, and all the media attention that they received for competing with Playboy, I rapidly became very well known as an erotic photographer of nudes. My career was greatly influenced by my affiliation with Penthouse and from that point on, hardly anybody remembered that I also did commercial work. A year before that, if you had told me a that I would become famous for shooting nudes, I wouldn’t have believed it.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Edu: You briefly mentioned Playboy, what took you to Playboy and how was it different from Penthouse?

Ken: There was a huge difference between Playboy and Penthouse at that time. Playboy had fought the battle to proclaim that “it’s alright to look at the nude body and not feel guilt about it” as though it was only art. Penthouse took the more progressive stance of “OK, now that you know it’s OK to look at a naked body, here’s some photos to turn you on.” Playboy wrote about sexuality while Penthouse presented it visually. It’s no wonder why Penthouse became so successful so quickly.

In those days, Playboy was showing only limited amounts of nudity in their magazine. They were presenting few pictorials of girls hiding behind brightly colored beach balls and other unrealistic and awkward situations, very much in the ’50s glamour style. Penthouse was featuring several pictorials in each issue that showed full nudity and models posed in more realistic sexual positions.

After 3 years of working with Penthouse, I had a disagreement over the amount of a reuse fee on one of my copyrighted images and decided to quit. That very same day, I went down the street and knocked on the doors of Playboy. I had shown up unannounced—I didn’t call or make an appointment and this rather snooty receptionist looked at me like, “What the hell do you want?” I told her I’d like to speak to Marilyn Grabowski, the west coast editor.

“Do you have an appointment?”

“No.”

“Does anyone know you’re coming?”

“No.”

“Well, what is your name?”

“Ken Marcus.”

She saunters off down the hall with this look on her face like she knew I’d never get to meet her boss, and then I hear this big commotion, and all of a sudden she’s running back. Her face is all red.

“Right this way Mr. Marcus.”

I walk into this magnificent office with incredible furniture and art work on the walls. Marilyn Grabowski had excellent and very expensive taste. She came over, shook my hand, asked me to sit down at this very beautiful desk and she points at my portfolio case.

“What’s that?” I tell her it’s my portfolio case.

“I brought it to show you what I do.”

She says, “I know what you do.” We sit down and, for the next 15 minutes she told me in exquisite detail, about the last 6 layouts of mine in Penthouse. Off the top of her head, she knew what my layouts were, what the girl looked like, her name, what the poses were, what the props were, what the lighting was. Marilyn knew more about my pictures than I did. I hadn’t been paying that much attention to what I did, really. After all, I was a young man concerned with making a living in commercial photography and was just banging out these layouts on the weekend. Marilyn Grabowski apparently had done her homework and knew exactly what her competition was up to and committed it to memory.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

I had no clue what I was in for… I thought this was just going to be another fun thing to do one weekend a month. Next thing I knew Playboy let go a bunch of their photographers, and for the next 11 years I got as much work as I could handle. During my tenure with Playboy, I produced over 40 centerfolds and at least 100 calendars, in addition to many editorials and covers. I averaged 280 days a year working on assignments.

As a businessman, I was extremely lucky as this move to Playboy coincided time-wise with an industry recession. The entire west coast advertising business fell apart. Ad agencies in Los Angeles were closing their doors or consolidating and moving to San Francisco or Chicago, and the business I had been doing well at for several years dwindled down. There just wasn’t lot of work for photographers at that particular time. But Playboy was keeping up with whatever I wanted to do. I could be as busy as I wanted to be. As soon as I finished one assignment they offered me 5 more, asking “Which one do you want?” This was during Playboy’s financial heyday, when they had more money than they could possibly think of spending, and we had “unlimited budgets.” I can’t even begin to explain what that means from a creative standpoint.

Edu: So you went from a $250 budget to an unlimited budget.

Ken: Yes, spending as much time and resources as needed to produce top quality layouts for the magazine. Not thinking of budgets as long as I could say, “Yes, we needed that prop, or that location for that pictorial.” Playboy was the most opulent of clients one could have at that time.

When I first agreed to work with Playboy, they flew out several of their editors to meet with me at Marilyn Grabowski’s office.

I remember thinking to myself, “Well, okay, I’ve been in a lot of corporate client meetings, I know what to expect. I’ll go in with a pad of paper and a pen to take notes. They will tell me what they need and what they expect of me.” I thought they’d tell me they need so many horizontal pictures, so many vertical pictures, butt shots, nudes, clothed shots, head shots, whatever it was that they required for their pictorials. I was prepared to take notes of what I was supposed to be doing for them.

An hour and a half later, when the meeting was over, I came out of there, and what was written on that piece of paper—which I still have somewhere in this studio, was:

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Edu: That has to be one of the greatest job descriptions of all time!

Ken: It certainly was. In those days Playboy owned a casino that was bringing in roughly a million dollars a day in revenue, and we could spend whatever was needed to produce the pictorials. After all, the centerfolds and pictorials were Playboy’s main product, and the entire enterprise depended on those images.

Without the pictures of the girls, what do they have? I mean, yes, everybody liked the articles, and I’m sure Mr. Hefner at that time believed that was why people read his magazine, but really as anyone knows, it was all about the girls. At that time there were very few photographers that were capable of doing that kind of photography—you could count all of them, in the world, on two hands. High-end glamour photography was a highly specialized field.

This was in the days before digital. There were no shortcuts. You had to be technically right-on with what you did, or your results would fail. If you were 1/3 of an f-stop off you were screwed. You had to understand complex lighting, and all of the technical aspects involved in producing glamour layouts. Any little variance would result in having to do a reshoot. We would work with anywhere between a three to eleven person crew. That’s what was necessary in those days, in order to produce those shoots.

For eight years, in addition to my other assignments, I exclusively shot the Playboy Calendar, which required building complicated sets in my studio and shooting 18 Playmates every year, so that Mr. Hefner could pick the final 12 that would get published in the calendar.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

The Model interview: Ken Marcus (part II)

In addition to his photographic career, Ken produced lectures, educational videos and conducted workshops on the art of glamour photography. His fine-art work has been featured in galleries, books, magazines, television, and he was an artist-in-residence at the Yosemite National Park Museum.

We recently had the pleasure of spending an afternoon with Ken at his Melrose Avenue studio. In part one of this two-part interview we talk to Ken about his early career.

– Edu

Actor Robert Blake shot on 8x10 on a freezing morning in Monument Valley for a movie billboard (Electra Glide in Blue).

Edu: Tell us about how you got into photography, in particular the time you spent at Yosemite National Park with Ansel Adams.

Ken Marcus: Well, there were two phases of my life that involved Yosemite. One was in my early life, and the other when I was in my 40s.

I began my association with Ansel Adams by attending one of his workshops at age 12. I fell in love with photography and continued to attend workshops at every opportunity. I spent every available moment that I was away from school either in Yosemite learning the Zone System and practicing landscape photography, or in my darkroom at home developing and printing the images I shot. I attended workshops all throughout my school years and even after I opened my studio and was making my living in photography. There was a great deal to learn and experience. However, after 13 years, I began to feel like somewhat of a distraction to the class and stopped attending Ansel’s workshops.

Edu: Why did you feel like you were a distraction?

Ken: Here were these other photographers coming from all over the world to study with Ansel, and when they realized there was a Playboy photographer in their group they started asking me lots of questions that did not relate to what the workshops were supposed to be about. That was understandable, but I didn’t feel that I should infringe on Ansel’s time. So, at that point I stopped attending his workshops and the following year I began teaching seminars and workshops of my own, and continued doing so for about another 25 years.

Edu: You started so young, and with Ansel Adams no less. How did that happen and what was it like?

Ken: Ansel was an amazing human being with this wonderful grey haired wife that used to cook and bake on a wood-burning stove in their Yosemite cabin. I remember thinking of them like Santa Claus and Mrs. Claus. Of course, I never told them that.

I started taking pictures when I was about 5 years old and took to it right away. I had a small darkroom in the basement and later my dad built one for me in the garage.

Some things never change: Ken at age 5

“I began my association with Ansel Adams by attending one of his workshops at age 12. I fell in love with photography and continued to attend workshops at every opportunity. I spent every available moment that I was away from school either in Yosemite learning the Zone System and practicing landscape photography, or in my darkroom at home developing and printing the images I shot.”I really started getting serious about photography when I started junior high school. It was at that point my parents enrolled me in an Ansel Adams workshop.

At the time, I don’t think they had any idea how famous he would eventually become. This was right at a crucial point in his career, when he was recognized by the small inner circles of the fine art community, but Ansel hadn’t really become a household name yet. I was studying with him throughout many of those years as his reputation, name and publicity continued to grow. I learned an enormous amount from him, both technically and philosophically, I learned about business and the importance of self-promotion, as well as other important things that have helped me make wise decisions throughout my career.

Edu: In addition to Ansel, you also studied at the Art Center College of Design as well as Brooks Institute of Photography.

Ken: I was studying with Ansel while I was in junior high school, and then all throughout high school. The Art Center College of Design is here in Southern California, and they offered a night program. You had to be a high school graduate with a couple years of college to qualify for that. Ansel was kind enough to write a very nice letter of introduction to let these people know that even though I was very young, I could function on an adult level and recommended they allow me to attend classes there.

So, for three years I attended night classes at the Art Center College of Design. I studied fashion, product design, architectural photography, product photography, food photography, and classical nude photography—all of the same curriculum that they had for their full time students.

When I graduated high school I just assumed I would go straight into Art Center full time, but they informed me that I still needed to have two years of college. I decided I didn’t want to do that, so I went up to Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara. I attended Brooks for a few semesters, and soon felt that between what I had learned at Brooks, Art Center and Ansel Adams there was no need to continue. So, at the ripe old age of 17 I acquired my business license, began working, and then a year later I found my studio. Two weeks after my 18th birthday I moved in, and I’ve been here ever since!

Edu: That’s an impressive story. You were obviously very entrepreneurial to start a business at 17. What role did your parents play, were you following in their footsteps somehow?

Ken: I come from a family where everyone is either an educator or a doctor. My mother was a political science professor in the state university system, and everyone else in my family are either doctors or associated with the medical profession. There are no other artists in my family. I somehow ended up being the only one.

Edu: That must have been hard for them to understand. Did they even consider photography a real career? Were they supportive?

Ken: They were extremely supportive. Photography is not an inexpensive hobby for a child to have, particularly in the days of film, and the necessity to have a dark room with enlargers, and all of those costly items that go along with it.

When I was 15 or so, my father met a man named Haskell Wexler. Haskell was an award-winning cinematographer and famous director, who did a lot of movies in the ’60s and ’70s. My father was telling him about me, and that I was interested in photography. He was worried that there was no future in taking pictures for a living and asked, “Can somebody actually make a living at this?”

My father told him about my attending Art Center and the Ansel Adams workshops. Haskell was very encouraging and related what he knew about the business and how it’s important to believe in my talent and that it usually takes a long time for things to happen in the photo business.

That conversation changed my father’s attitude. At least now he knew that maybe there was hope, and that his son might actually make a living with his camera. He realized at that point, it’s not just a hobby, like he might have previously thought. That was one of those pivotal events that I look back on, that was very important in my life.

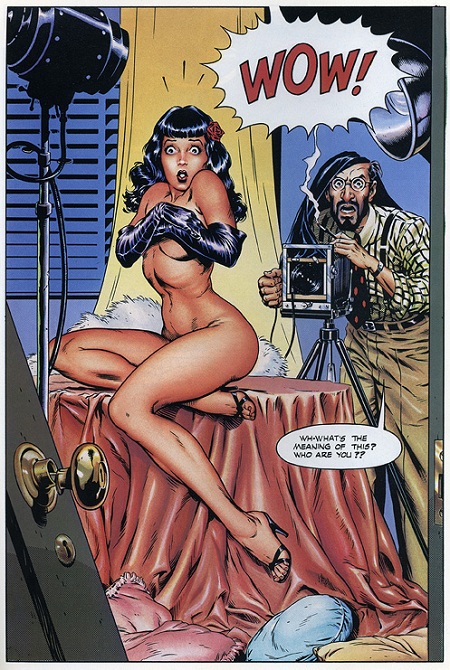

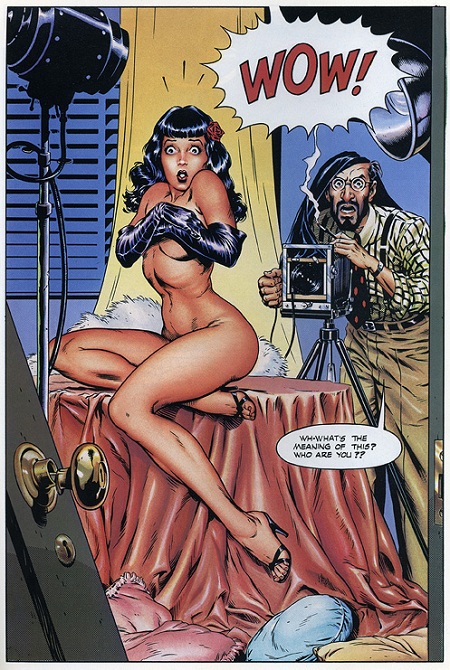

Ken was the inspiration for the villain "Marco of Hollywood" in the comic book series, "The Rocketeer" created by his longtime friend, Dave Stevens.

Edu: Okay, so now your family is on board, and obviously you’re already very talented, but when was the turning point where you actually started making a living and photography became your career?

Ken: I started earning money with my camera within the first month of getting my business license. I was still living at my parents house and was sharing a studio with my friend Don Carroll, who did special effects photography.

My very first job was to photograph a lamp for a local store. For whatever reason they trusted this skinny 17-year-old to photograph their lamp for a newspaper ad. I did such a good job, that I was then immediately given my second assignment, photographing their entire lamp catalog. I went from photographing one lamp to photographing 150 lamps. It put good money in my pocket, which was nice, and then as life sometimes does, you get thrown a strange curveball.

Out of the blue, my very next assignment came in as a recommendation from the lamp client to his friend that owned a burlesque theater in Hollywood. The next thing I know, I was photographing the instruction book for the Pink Pussycat College of Striptease, where beautiful women came from all over the world to learn the fine art of peeling off a glove, 20 different ways of taking off a stocking, how to tease an audience, and how to prance across the stage and all the refinements of burlesque dancing.

Edu: And you were 17-18 years old when this job came up?

Ken: I was 17 years old then. I wasn’t old enough to go into a burlesque theater as a patron, but here I was shooting the most amazing burlesque dancers for the most notorious strip joint in Hollywood. I was working with famous dancers from all over the world. Dancers in those days weren’t like anything we have today. Total nudity was completely illegal everywhere in America, but for a 17-year-old, it was still more than anything I had encountered before. Funny how things work out!

From there I went on to shooting more lamps, products, architecture, advertising and food. I think I made more money shooting food on a daily basis than any other kind of assignment I ever did.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Edu: We know you eventually went on to shoot for Penthouse, which I assume was far more controversial back then. Did it ever get in the way of your commercial work?

Ken: Not to any real extent. I’m sure that some of the women I was working with at ad agencies might have been uncomfortable if they knew I was shooting for Penthouse, but it never came back to bite me in the butt or anything, and no one ever confronted me or said “You’re an evil, horrible person.” I’m not sure any of my commercial clients even knew what I was doing.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Edu: Speaking of Penthouse, tell us about your time there. What inspired your use of soft-focus photography, and how did you do it?

Ken: When I started working at Penthouse in the early 70s they had very low budgets. My reason for working with them was because I thought it would be fun. It seemed like a nice excuse to shoot pretty naked girls one weekend a month, and I figured it wouldn’t really interfere with my commercial work. However, I was a little concerned because I wasn’t sure how people would respond to my shooting nudes. I wasn’t smart enough back then to think, “Geez, maybe I should just use another name like most other people in this line of work do.”

Instead, I thought I’d disguise my style so no one will know the work is mine, which was very stupid because I didn’t really have a style at the time. I was doing the same sort of photography as everyone else was doing at the time—sharp, crisp, well-lit images, with all information available within the image. That’s what everybody was doing and that’s just what I was doing as well.

I thought about what I could do to make my pictures different from all the others. The first challenge was to make the models and backgrounds look beautiful and sexy. Keep in mind that we didn’t have adequate budgets for fancy locations, wardrobe or nice props. The other problem was to hide that fact and still produce fantasy images on a really low budget.

The solution seemed to be the old fashioned, out of date technique of soft-focus imagery.

I had remembered an image that Ansel Adams had done on an 8×10 view camera with an old Kodak soft focus lens from the 1920s. Everything had this soft glow to it, and the highlights were bursting and burning out. It seemed sexy for some reason even though it was just rocks, trees and water. I thought, what better way to hide the lack of good makeup and props than to use a soft focus technique and concentrate on the sensuality of the model and the sexuality of the model? Let everything else blur out.

I remembered Ansel saying that you can achieve that effect without using a heavy, expensive soft-focus lens by putting a skylight filter in front of your lens and rubbing a little Vaseline on it.

So, for my very first Penthouse layout, I did just that, and Bob Guccione (founder and owner of Penthouse) loved the results and encouraged me to do more. For the next three years almost every layout I did was soft focus. Actually, it’s not really soft focus. Your focus still has to be on, but it’s diffusion. Being out of focus is much different than being diffused, but a lot of people don’t get that. Those diffused images became known as the “Penthouse look” and that different style of imagery rapidly became very popular and gave my name a lot of national exposure.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

“I thought about what I could do to make my pictures different from all the others. The first challenge was to make the models and backgrounds look beautiful and sexy.”I learned the hard way that if you smear Vaseline on a piece of glass and then put it back in your camera case it makes a mess, so I looked for other other materials to use. In those days there was black and white Polaroid that had these little coater brushes that you would smear across the image after it was developed, to sort of affix it onto the paper. It was a clear substance that dried rather quickly, so I experimented and applied some to a skylight filter and then put it in front of my lens. It created the very same effect as the Vaseline except it was dry, so I could now put it in my camera case and use it again and again. I made about 10 of them in different configurations and patterns, little dots and crisscrosses and all of that.

Later on I began experimenting with fabric and cloth because I heard somewhere if you stretch a silk stocking over a lens it will create a diffusion effect. I found a variety of stocking material, and loose weave scarf material in black, because white flared things out. Flesh color was nice for some things but it threw the contrast off. Black stockings and loose weave scarf material worked best for me, so I made a series of diffusion filters like that, and continued to use those for many years. Almost everything I shot for Playboy for 11 years was with those black scarf-type diffusers.

Edu: So the inspiration for that technique, came in part from Ansel, but what about the other ones? This was long before the Internet, how did you come up with these ideas?

Ken: I don’t suddenly wake up and think, “Oh this is new, this is different, and this is what I’m going to do next.” I mean, I might wake up in the morning with that, but it’s because when I went to bed I were thinking of ten other things that also could have gelled together.

We don’t live in a vacuum; you have to learn from somewhere. I’ve always felt that everything I’ve ever done, or whatever I’ve ever come up with, has been a result of learning from others. That realization motivated me to get into the teaching aspect of photography where I could pass on the information I’ve learned. I feel that if you learn something that benefits your life, there is an obligation to pass that information on to others.

Edu: Some people are reluctant to share knowledge, like they’re scared of revealing the secret to their success, or they view everyone else as competition.

Ken: I believe in passing on what I have learned from others. When I take the time to instruct others in what I do, it clarifies in my mind what it is that I really do. Passing on the information benefits me in that way. Sometimes you don’t really appreciate the intricacies of what you do, until you try to teach it to others. Besides, knowing something in a technical realm doesn’t really make you successful. You may be very talented, with strokes of occasional brilliance, but if you can’t manage or deal with people, your work will never be seen, it’s just not going to happen. Being successful in business requires people skills, and for some reason a lot of people just don’t get it. Success is the proper combination of talent, technique, people skills, and a lot of luck.

Photo of Ken Marcus by Tom Zimberoff

“I believe in passing on what I have learned from others. When I take the time to instruct others in what I do, it clarifies in my mind what it is that I really do. Passing on the information benefits me in that way.”Edu: What was that like to be shooting for Penthouse?

Ken: When Bob Guccione first spoke to me about shooting for him I asked what the budget was for a pictorial. He said we have $250, and that has to include the model. At first that sounded ridiculous, because I was making thousands of dollars a day shooting food ads, but then I reasoned that it might be fun, and would be a good excuse to shoot more nudes.

I almost decided to say no because of the low budget. Then all of a sudden out of nowhere, I got this inspiration from something Ansel Adams once told me, “It’s okay to give your pictures away for free as long as you get a photo credit on the page with the pictures.”

So I followed my instincts and said to Guccione, “Okay I’ll do it, but I want a photo credit on the first page of each pictorial.” All I was expecting was small text on the bottom of the page that said “Photo by Ken Marcus.” In those days photographers did not get photo credits on the pictures unless it was a big deal, like some photographer for Life magazine covering a war somewhere. Everybody else had photo credits listed in a box in page 3. Sometimes you couldn’t even figure out which photographer took which pictures. That’s what publications did in those days.

So I asked for a photo credit and Bob said, “Sure, no problem.” When my first issue of Penthouse came out in the U.S., I was very surprised and amazed. Instead of a single right hand page that would open up into a layout, which was standard in those days. It was a double page spread with one picture covering both pages, which also was really rare and highly unusual at that time, and right through the middle of the picture, in text that was ¾ of an inch high, it said “Photographed by Ken Marcus.” It blew me away. I was not expecting that.

For the next three years each of my layouts had these giant photo credits on them. With the overnight success of Penthouse, and all the media attention that they received for competing with Playboy, I rapidly became very well known as an erotic photographer of nudes. My career was greatly influenced by my affiliation with Penthouse and from that point on, hardly anybody remembered that I also did commercial work. A year before that, if you had told me a that I would become famous for shooting nudes, I wouldn’t have believed it.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

Edu: You briefly mentioned Playboy, what took you to Playboy and how was it different from Penthouse?

Ken: There was a huge difference between Playboy and Penthouse at that time. Playboy had fought the battle to proclaim that “it’s alright to look at the nude body and not feel guilt about it” as though it was only art. Penthouse took the more progressive stance of “OK, now that you know it’s OK to look at a naked body, here’s some photos to turn you on.” Playboy wrote about sexuality while Penthouse presented it visually. It’s no wonder why Penthouse became so successful so quickly.

In those days, Playboy was showing only limited amounts of nudity in their magazine. They were presenting few pictorials of girls hiding behind brightly colored beach balls and other unrealistic and awkward situations, very much in the ’50s glamour style. Penthouse was featuring several pictorials in each issue that showed full nudity and models posed in more realistic sexual positions.

After 3 years of working with Penthouse, I had a disagreement over the amount of a reuse fee on one of my copyrighted images and decided to quit. That very same day, I went down the street and knocked on the doors of Playboy. I had shown up unannounced—I didn’t call or make an appointment and this rather snooty receptionist looked at me like, “What the hell do you want?” I told her I’d like to speak to Marilyn Grabowski, the west coast editor.

“Do you have an appointment?”

“No.”

“Does anyone know you’re coming?”

“No.”

“Well, what is your name?”

“Ken Marcus.”

She saunters off down the hall with this look on her face like she knew I’d never get to meet her boss, and then I hear this big commotion, and all of a sudden she’s running back. Her face is all red.

“Right this way Mr. Marcus.”

I walk into this magnificent office with incredible furniture and art work on the walls. Marilyn Grabowski had excellent and very expensive taste. She came over, shook my hand, asked me to sit down at this very beautiful desk and she points at my portfolio case.

“What’s that?” I tell her it’s my portfolio case.

“I brought it to show you what I do.”

She says, “I know what you do.” We sit down and, for the next 15 minutes she told me in exquisite detail, about the last 6 layouts of mine in Penthouse. Off the top of her head, she knew what my layouts were, what the girl looked like, her name, what the poses were, what the props were, what the lighting was. Marilyn knew more about my pictures than I did. I hadn’t been paying that much attention to what I did, really. After all, I was a young man concerned with making a living in commercial photography and was just banging out these layouts on the weekend. Marilyn Grabowski apparently had done her homework and knew exactly what her competition was up to and committed it to memory.

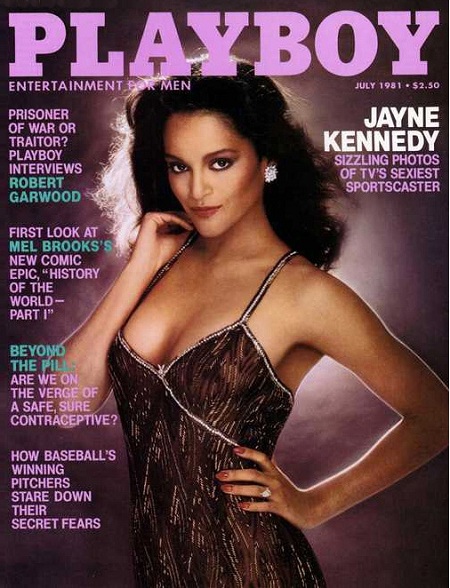

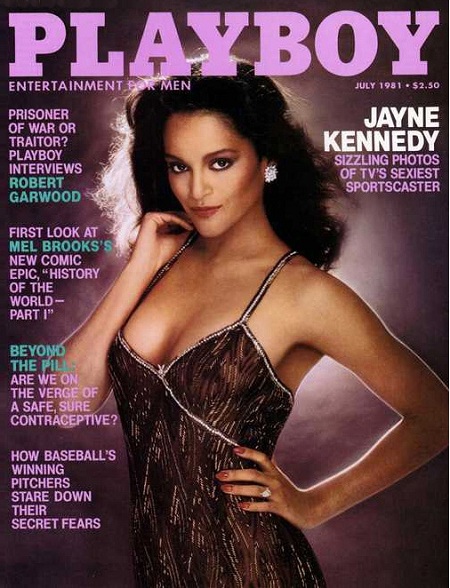

One of over a hundred studio images Ken produced for the Playboy Calendar project.

“After 3 years of working with Penthouse, I had a disagreement over the amount of a reuse fee on one of my copyrighted images and decided to quit. That very same day, I went down the street and knocked on the doors of Playboy.”I later learned that during the time I was working with Penthouse, their circulation rose from 350,000 to 4.5 million, while Playboy’s circulation dropped substantially. Apparently Playboy was attributing this circulation drop to the different way Penthouse looks and what they stood for, versus what Playboy looks like. I was told that Playboy had tried to get their photographers to learn how to shoot in this new erotic, soft focus style, and for whatever reason, they just couldn’t do it. So, when I approached Playboy they were really happy to see me.

I had no clue what I was in for… I thought this was just going to be another fun thing to do one weekend a month. Next thing I knew Playboy let go a bunch of their photographers, and for the next 11 years I got as much work as I could handle. During my tenure with Playboy, I produced over 40 centerfolds and at least 100 calendars, in addition to many editorials and covers. I averaged 280 days a year working on assignments.

As a businessman, I was extremely lucky as this move to Playboy coincided time-wise with an industry recession. The entire west coast advertising business fell apart. Ad agencies in Los Angeles were closing their doors or consolidating and moving to San Francisco or Chicago, and the business I had been doing well at for several years dwindled down. There just wasn’t lot of work for photographers at that particular time. But Playboy was keeping up with whatever I wanted to do. I could be as busy as I wanted to be. As soon as I finished one assignment they offered me 5 more, asking “Which one do you want?” This was during Playboy’s financial heyday, when they had more money than they could possibly think of spending, and we had “unlimited budgets.” I can’t even begin to explain what that means from a creative standpoint.

Edu: So you went from a $250 budget to an unlimited budget.

Ken: Yes, spending as much time and resources as needed to produce top quality layouts for the magazine. Not thinking of budgets as long as I could say, “Yes, we needed that prop, or that location for that pictorial.” Playboy was the most opulent of clients one could have at that time.

When I first agreed to work with Playboy, they flew out several of their editors to meet with me at Marilyn Grabowski’s office.

I remember thinking to myself, “Well, okay, I’ve been in a lot of corporate client meetings, I know what to expect. I’ll go in with a pad of paper and a pen to take notes. They will tell me what they need and what they expect of me.” I thought they’d tell me they need so many horizontal pictures, so many vertical pictures, butt shots, nudes, clothed shots, head shots, whatever it was that they required for their pictorials. I was prepared to take notes of what I was supposed to be doing for them.

An hour and a half later, when the meeting was over, I came out of there, and what was written on that piece of paper—which I still have somewhere in this studio, was:

- Travel first class, stay only in the finest hotels.

- Eat at the best restaurants.

- When you travel, make sure our publicity department knows where you are going so that they can let everybody know who you are, and why you are there.

- Tip big, so nobody steals your stuff.

- And whatever else you do, always make sure that you look like you’re having a great time.

The 50 story Playboy building rooftop, taken from the 90th floor of the John Hancock building. More than a hundred women lit with over 30 strobes, triggered by infra-red from two blocks away.

Edu: That has to be one of the greatest job descriptions of all time!

Ken: It certainly was. In those days Playboy owned a casino that was bringing in roughly a million dollars a day in revenue, and we could spend whatever was needed to produce the pictorials. After all, the centerfolds and pictorials were Playboy’s main product, and the entire enterprise depended on those images.

Without the pictures of the girls, what do they have? I mean, yes, everybody liked the articles, and I’m sure Mr. Hefner at that time believed that was why people read his magazine, but really as anyone knows, it was all about the girls. At that time there were very few photographers that were capable of doing that kind of photography—you could count all of them, in the world, on two hands. High-end glamour photography was a highly specialized field.

This was in the days before digital. There were no shortcuts. You had to be technically right-on with what you did, or your results would fail. If you were 1/3 of an f-stop off you were screwed. You had to understand complex lighting, and all of the technical aspects involved in producing glamour layouts. Any little variance would result in having to do a reshoot. We would work with anywhere between a three to eleven person crew. That’s what was necessary in those days, in order to produce those shoots.

For eight years, in addition to my other assignments, I exclusively shot the Playboy Calendar, which required building complicated sets in my studio and shooting 18 Playmates every year, so that Mr. Hefner could pick the final 12 that would get published in the calendar.

Photographer: Ken Marcus

“This was in the days before digital. There were no shortcuts. You had to be technically right-on with what you did, or your results would fail. If you were 1/3 of an f-stop off you were screwed. You had to understand complex lighting, and all of the technical aspects involved in producing glamour layouts.”–

The Model interview: Ken Marcus (part II)

No comments:

Post a Comment